Making Information Make Sense

InfoMatters

Category: General / Topics: Internet • Planning • Policy • Science & Technology • Social Movements • Trends

Unintended Consequences, Number 3

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: December 353, 2018

#MeToo, Cybercurrency, and the Cloud

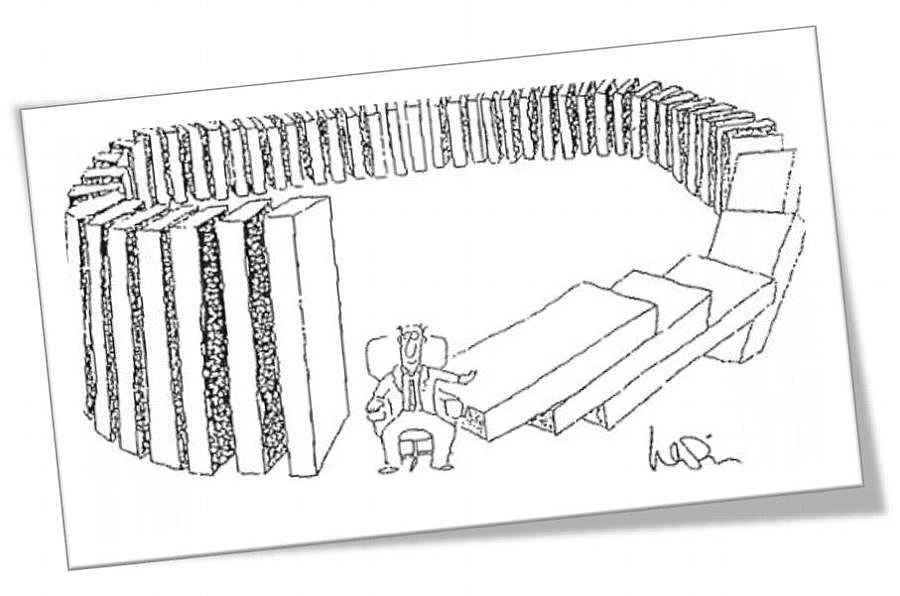

Social movements and innovation, while aimed at progress or correction, often have unintended consequences that blunt their impact or, in some case, make matters worse. This is the latest in a growing collection of blogs on the subject. It was inspired by two things: a recent column by Kathleen Parker on the #MeToo movement, and a discussion about cybercurrency in an adult class at the church I attend.

The inevitable unintended consequences of #MeToo

That was the title of Kathleen Parker’s December 4 column in the Washington Post. Here is an excerpt:

A recent Bloomberg News headline came as no surprise: “Wall Street Rule for the #MeToo Era: Avoid Women at All Cost.”

In a word, it was inevitable. Some men are so concerned about the possible repercussions of what they might say or do that they’re steering clear of women in the workplace altogether. And as a result, according to the report, Wall Street “risks becoming more of a boy’s club, rather than less of one.”

The article focused on the various ways some senior executives in finance have been “spooked” by #MeToo and are “struggling to cope” — resorting to staying on different hotel floors from women when on business trips, not dining alone with any woman 35 or younger, leaving an office door open when meeting one-on-one with a junior female. Generally speaking, these might not be such bad rules but for the fact that, as Bloomberg News pointed out, young women often need mentors to advance and female executives are far scarcer than men on Wall Street. And as one wealth adviser said, simply hiring a woman has become “an unknown risk.”

The story called these collateral adjustments the “Pence Effect,” referring to Vice President Pence’s personal rule of not dining alone with a woman who isn’t his wife.. . . Further, to be fair, these newly devised workplace protocols are not primarily a function of paranoia but of reality. . . . Even casual interactions can seem unnecessarily risky.And this new reality isn’t limited to the world of finance. Many men across all industries now fear being alone with a female colleague.

. . . Perceptions have changed significantly the past several decades, for the good, but we still have much work to do in defining what is and isn’t “abuse.”

In many ways, this is all new terrain for us societally: How do we balance the right of every individual to be believed innocent until proven otherwise, while also giving accusers a platform to be heard? The recent Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Brett M. Kavanaugh highlighted the impossible position of being forced to prove one’s innocence against accusations backed by no verifiable evidence. We should sleep uneasily in the wake of such an abuse of due process, not as a legal matter but as a time-honored principle of fairness.

We’ve yet to see the full spectrum of collateral damage to come, but we’ve gotten a sense of its scope. Already, some men are silencing themselves rather than engaging in a losing battle. Several have told me that, like the wealth adviser Bloomberg News interviewed, they’re more hesitant to hire women or even to be alone with them. My orthopedist tells me he’s no longer comfortable hugging his patients, as he’d always done. . . .

Many men are so intimidated by the #MeToo movement and the plausibility that they, too, could be ruined on the basis of a single woman’s misinterpretation of an innocent gesture that they’re essentially shutting down and stepping away. Suffice it to say, this side effect won’t serve women well in the long run. Indeed, it seems obvious that they’ll suffer.

There surely is a balance to be found lest the sexes further alienate and segregate. We should seek it with a sense of urgency.Read more from Kathleen Parker’s archive, follow her on Twitter or find her on Facebook.

Read more (from Parker’s online column):

Karen Tumulty: To the president, #MeToo is little more than a punchline

Daniel W. Drezner: #MeToo, one year later

Katharine Viles: I’m a sexual assault survivor. #MeToo is incredibly isolating.

Karen Tumulty: We’ve seen #MeToo gains. But also how fragile they are.

Jennifer Rubin: #MeToo needs to become #NotHim

Money without a bank

Cybercurrency (bitcoin and similar approaches) was the topic of one of the sessions in a class on “Living as a Christian in the Modern World” at the church I attend. The series has looked at social media, artificial intelligence, transhumanism, and other technological and philosophical movements affecting our culture and the impact on the expression of Christian faith. (My November 21 blog, “Driven Apart or Drawn Together,” relied in part on an earlier session on social media and public life).

Cybercurrency is a system that allows transactions of value without using traditional financial institutions. Reference was made to a technical white paper by Satoshi Nakamoto, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.” In the Abstract, Nakamoto explains the system:

A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online

payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution. Digital signatures provide part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required to prevent double-spending. We propose a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network. , , ,

The exchange of cybercurrency relies on a system of verification that avoids the banking system, but instead uses a technological solution to verify that the sender, recipient, amount and other details are valid. The approach is also known as “blockchain.” Worthy of additional discussion is the lack of trust in traditional institutions inherent in cybercurrency (dealt with, to some extent, in my March 6 blog on Trust.)

To put it simply (but risking technical inaccuracy), a long code—like a riddle—is sent to thousands of computers connected by the internet into a peer-to-peer network. Such a network is like a virtual supercomputer made up of many computers scattered around the world, all trying to solve the “riddle” for each transaction.

It is a brute force method that requires trying every one of billions of variations until the one that fits is found. Think of trying to guess a four-digit PIN number. There are 10,000 possibilities using numbers alone. If instead of numbers the code is made up of the full range of 256 numbers, letters and symbols that could be assigned to each position, the possibilities increase to 4,295,000,000. The cybercurrency riddle has so many possibilities, it can take up to ten minutes for all the computers active on the peer-to-peer network to find the correct solution. Only then can the transaction be authorized. The “node” finding the solution is awarded a fee.

When a flow chart depicting the process of a cybercurrency transaction was displayed, my eyes fell on the verification step that uses this large peer-to-peer network. With the amount of distributed computer power required, I wondered, “what is the carbon footprint” of verifying bitcoin and similar transactions?

Even if we’re talking about a bunch of people who each have only a few computers in their basements, consider the cumulative amount of computing power needed to solve all those riddles (transactions) each day. That translates into a lot of electrical power and heat. It may not be much at any one node on the network, but taken together, it could be comparable to or even exceed that of an actual supercomputer. (A supercomputer is not used, as I understand it, because the verification system relies on the independence of the distributed nodes).

The cybercurrency approach is supposed to be hacker-proof, though I wonder with others if the enormous interest shown by nation-players like Russia and China to “weaponize” the internet will keep that claim an absolute certainty. (See the section on “The Darkening Web” in my blog on Trust.) As I was finishing this blog, a report on Nightly Business Report focused on this very type of attack by the Chinese, using “crypto-mining.”

One of the consequences (unintended, hidden or ignored) of cybercurrency is the carbon footprint of the aggregate resources necessary. The irony is that many people enthralled with technology and concerned about climate change, are either unaware or ignorant of the impact of their own activity. The introduction of “The Cloud” is similar.

The carbon cloud

What comes to mind when you think of “The Cloud”? It has a magical ring. It sounds very innocuous. The Cloud is a term applied to a collection of large capacity data servers connected to the internet. The net effect is to move data from individual computers and networks to the internet, where it can be more easily accessed across devices and users.

While “the cloud” connotes a single, mammoth “server farm,” it is made up of numerous server farms around the world, each containing row upon row of racks filled with storage and routing devices, all connected by the internet. It is a concept that has taken on a cool nickname that obscures its true nature, which is that the data is now “out there,” somewhere and not on your local device. (It is possible to maintain a local copy and synchronize it with the cloud version. It is now common for software to give the option of local and/or cloud storage.)

Ever-increasing bandwidth (data-carrying capacity) of the internet along with faster and more powerful devices (from computers to smart phones) and cheap storage for ever-larger amounts of data have led to the exponential growth in the number of servers that make the cloud as ubiquitous as it is. That is where the unintended (or ignored or tolerated) consequences come in.

Moving data from your own computer to the cloud means it is going to a server farm, usually housed in a large building. That means a “brick and mortar” structure along with large amounts of electricity to power the servers and the air conditioning to cool them, with a significant carbon footprint. A friend mentioned driving around an industrial park and seeing what looked like a huge warehouse, except it did not have the usual row of loading docks. It was a server farm for Amazon.

I remember reading several years ago about Google’s plan to use barges as a location for server farms that could be water-cooled instead of requiring traditional energy-hungry air conditioning. (See “Google’s worst-kept secret: floating data centers off US coasts” in The Guardian, October 2013).

The issues discussed here are admittedly very complicated. You’ll find articles outlining the huge carbon costs of the cloud and internet while others suggesting that such technology can reduce carbon emissions, at least in the long haul.

The largest data storage companies are making attempts to use renewable energy and otherwise reduce their carbon footprint (though that can be done by purchasing carbon credits rather than making direct use of renewable energy). Six major cloud brands (Apple, Box, Facebook, Google, Rackspace, and Salesforce) have committed to powering data centers with 100% renewable energy by 2020.

Of course, renewable energy may have its own unintended consequences. While the direct result of the technology—wind, solar, water—may have a net zero or very low carbon footprint, like the buildings that house server farms, they are not without carbon-related factors. What must be considered, especially as renewable energy technology increases in scale, are factors such as the materials used, the manufacture of the devices, site acquisition and preparation, transportation to and installation at the site, maintenance—all of this on top of the costs (in dollars and CO2) of operating the electrical distribution system and the internet, since the largest wind and solar farms, and hydroelectric plants are far from the places where the electricity generated is needed. Also, think of the potential consequences as renewable energy generation requires more land. It is hard to imagine it as a zero-sum game.

Thinking small, learning from the past

While large-scale solutions are often the only resort, despite the associated environmental costs, I wonder about the alternative of small-scale, local solutions when that is an option. I don’t recall the details, but a PBS program on energy pointed out how one appliance manufacturer found that installing a large wind turbine at the factory made sense in controlling energy costs.

Moving to examples at the level of the individual house, years ago I was interested in solar energy, but our house faced the wrong direction and, frankly, solar at that time had a long way to go to be practical, whether it was used for generating electricity or hot water. However, with a big yard and garden, I developed a multi-bin compost system and later added multiple rain barrels at the back of the house. More recently, advances in computer technology--especially flat screen monitors— converstion to LED bulbs throughout the house, and similar measures have dramatically cut electric consumption. There are ways each of us can demonstrate environmental stewardship.

As solar and wind devices have become much more efficient and adaptable to smaller settings, it is possible to think of using them for individual homes, subdivisions or communities. This futuristic vision, however, is not new.

Kline Creek farm is an 1890s farm near us that has been preserved and used to show what life on the farm was like back then. For all the modern talk of sustainability and attention to the environment, I am always impressed with how self-supporting that farm was. For example, a windmill pumped water into a tank that kept milk cans cool while waiting to be taken to market. From there the water flowed downward to fill water troughs for the animals in the barn and on to outdoor pens. A detached summer kitchen kept heat out of the house during hot months, while the kitchen stove helped provide heat inside the house in cold months. A cistern under part of the house collected rainwater to provide “grey water” for washing and bathing.

Why not use that sense of self-sufficiency and sustainability closer to home?

Back to the Cloud

Ok, I’m drifting away from the focus on The Cloud, but all these issues of resource use are interconnected. Besides, even if electric generation could be done closer to where it is used, the very nature of the internet requires vast infrastructure to connect the world.

For a good overview on this complex issue, see the infographic “The Carbon Footprint of the Internet” on climatecare.com.

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: December 353, 2018 Accessed 2,681 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...InfoMatters

Category: General / Topics: Internet • Planning • Policy • Science & Technology • Social Movements • Trends

Unintended Consequences, Number 3

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: December 353, 2018

#MeToo, Cybercurrency, and the Cloud

Social movements and innovation, while aimed at progress or correction, often have unintended consequences that blunt their impact or, in some case, make matters worse. This is the latest in a growing collection of blogs on the subject. It was inspired by two things: a recent column by Kathleen Parker on the #MeToo movement, and a discussion about cybercurrency in an adult class at the church I attend.

The inevitable unintended consequences of #MeToo

That was the title of Kathleen Parker’s December 4 column in the Washington Post. Here is an excerpt:

A recent Bloomberg News headline came as no surprise: “Wall Street Rule for the #MeToo Era: Avoid Women at All Cost.”

In a word, it was inevitable. Some men are so concerned about the possible repercussions of what they might say or do that they’re steering clear of women in the workplace altogether. And as a result, according to the report, Wall Street “risks becoming more of a boy’s club, rather than less of one.”

The article focused on the various ways some senior executives in finance have been “spooked” by #MeToo and are “struggling to cope” — resorting to staying on different hotel floors from women when on business trips, not dining alone with any woman 35 or younger, leaving an office door open when meeting one-on-one with a junior female. Generally speaking, these might not be such bad rules but for the fact that, as Bloomberg News pointed out, young women often need mentors to advance and female executives are far scarcer than men on Wall Street. And as one wealth adviser said, simply hiring a woman has become “an unknown risk.”

The story called these collateral adjustments the “Pence Effect,” referring to Vice President Pence’s personal rule of not dining alone with a woman who isn’t his wife.. . . Further, to be fair, these newly devised workplace protocols are not primarily a function of paranoia but of reality. . . . Even casual interactions can seem unnecessarily risky.And this new reality isn’t limited to the world of finance. Many men across all industries now fear being alone with a female colleague.

. . . Perceptions have changed significantly the past several decades, for the good, but we still have much work to do in defining what is and isn’t “abuse.”

In many ways, this is all new terrain for us societally: How do we balance the right of every individual to be believed innocent until proven otherwise, while also giving accusers a platform to be heard? The recent Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Brett M. Kavanaugh highlighted the impossible position of being forced to prove one’s innocence against accusations backed by no verifiable evidence. We should sleep uneasily in the wake of such an abuse of due process, not as a legal matter but as a time-honored principle of fairness.

We’ve yet to see the full spectrum of collateral damage to come, but we’ve gotten a sense of its scope. Already, some men are silencing themselves rather than engaging in a losing battle. Several have told me that, like the wealth adviser Bloomberg News interviewed, they’re more hesitant to hire women or even to be alone with them. My orthopedist tells me he’s no longer comfortable hugging his patients, as he’d always done. . . .

Many men are so intimidated by the #MeToo movement and the plausibility that they, too, could be ruined on the basis of a single woman’s misinterpretation of an innocent gesture that they’re essentially shutting down and stepping away. Suffice it to say, this side effect won’t serve women well in the long run. Indeed, it seems obvious that they’ll suffer.

There surely is a balance to be found lest the sexes further alienate and segregate. We should seek it with a sense of urgency.Read more from Kathleen Parker’s archive, follow her on Twitter or find her on Facebook.

Read more (from Parker’s online column):

Karen Tumulty: To the president, #MeToo is little more than a punchline

Daniel W. Drezner: #MeToo, one year later

Katharine Viles: I’m a sexual assault survivor. #MeToo is incredibly isolating.

Karen Tumulty: We’ve seen #MeToo gains. But also how fragile they are.

Jennifer Rubin: #MeToo needs to become #NotHim

Money without a bank

Cybercurrency (bitcoin and similar approaches) was the topic of one of the sessions in a class on “Living as a Christian in the Modern World” at the church I attend. The series has looked at social media, artificial intelligence, transhumanism, and other technological and philosophical movements affecting our culture and the impact on the expression of Christian faith. (My November 21 blog, “Driven Apart or Drawn Together,” relied in part on an earlier session on social media and public life).

Cybercurrency is a system that allows transactions of value without using traditional financial institutions. Reference was made to a technical white paper by Satoshi Nakamoto, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.” In the Abstract, Nakamoto explains the system:

A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online

payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution. Digital signatures provide part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required to prevent double-spending. We propose a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network. , , ,

The exchange of cybercurrency relies on a system of verification that avoids the banking system, but instead uses a technological solution to verify that the sender, recipient, amount and other details are valid. The approach is also known as “blockchain.” Worthy of additional discussion is the lack of trust in traditional institutions inherent in cybercurrency (dealt with, to some extent, in my March 6 blog on Trust.)

To put it simply (but risking technical inaccuracy), a long code—like a riddle—is sent to thousands of computers connected by the internet into a peer-to-peer network. Such a network is like a virtual supercomputer made up of many computers scattered around the world, all trying to solve the “riddle” for each transaction.

It is a brute force method that requires trying every one of billions of variations until the one that fits is found. Think of trying to guess a four-digit PIN number. There are 10,000 possibilities using numbers alone. If instead of numbers the code is made up of the full range of 256 numbers, letters and symbols that could be assigned to each position, the possibilities increase to 4,295,000,000. The cybercurrency riddle has so many possibilities, it can take up to ten minutes for all the computers active on the peer-to-peer network to find the correct solution. Only then can the transaction be authorized. The “node” finding the solution is awarded a fee.

When a flow chart depicting the process of a cybercurrency transaction was displayed, my eyes fell on the verification step that uses this large peer-to-peer network. With the amount of distributed computer power required, I wondered, “what is the carbon footprint” of verifying bitcoin and similar transactions?

Even if we’re talking about a bunch of people who each have only a few computers in their basements, consider the cumulative amount of computing power needed to solve all those riddles (transactions) each day. That translates into a lot of electrical power and heat. It may not be much at any one node on the network, but taken together, it could be comparable to or even exceed that of an actual supercomputer. (A supercomputer is not used, as I understand it, because the verification system relies on the independence of the distributed nodes).

The cybercurrency approach is supposed to be hacker-proof, though I wonder with others if the enormous interest shown by nation-players like Russia and China to “weaponize” the internet will keep that claim an absolute certainty. (See the section on “The Darkening Web” in my blog on Trust.) As I was finishing this blog, a report on Nightly Business Report focused on this very type of attack by the Chinese, using “crypto-mining.”

One of the consequences (unintended, hidden or ignored) of cybercurrency is the carbon footprint of the aggregate resources necessary. The irony is that many people enthralled with technology and concerned about climate change, are either unaware or ignorant of the impact of their own activity. The introduction of “The Cloud” is similar.

The carbon cloud

What comes to mind when you think of “The Cloud”? It has a magical ring. It sounds very innocuous. The Cloud is a term applied to a collection of large capacity data servers connected to the internet. The net effect is to move data from individual computers and networks to the internet, where it can be more easily accessed across devices and users.

While “the cloud” connotes a single, mammoth “server farm,” it is made up of numerous server farms around the world, each containing row upon row of racks filled with storage and routing devices, all connected by the internet. It is a concept that has taken on a cool nickname that obscures its true nature, which is that the data is now “out there,” somewhere and not on your local device. (It is possible to maintain a local copy and synchronize it with the cloud version. It is now common for software to give the option of local and/or cloud storage.)

Ever-increasing bandwidth (data-carrying capacity) of the internet along with faster and more powerful devices (from computers to smart phones) and cheap storage for ever-larger amounts of data have led to the exponential growth in the number of servers that make the cloud as ubiquitous as it is. That is where the unintended (or ignored or tolerated) consequences come in.

Moving data from your own computer to the cloud means it is going to a server farm, usually housed in a large building. That means a “brick and mortar” structure along with large amounts of electricity to power the servers and the air conditioning to cool them, with a significant carbon footprint. A friend mentioned driving around an industrial park and seeing what looked like a huge warehouse, except it did not have the usual row of loading docks. It was a server farm for Amazon.

I remember reading several years ago about Google’s plan to use barges as a location for server farms that could be water-cooled instead of requiring traditional energy-hungry air conditioning. (See “Google’s worst-kept secret: floating data centers off US coasts” in The Guardian, October 2013).

The issues discussed here are admittedly very complicated. You’ll find articles outlining the huge carbon costs of the cloud and internet while others suggesting that such technology can reduce carbon emissions, at least in the long haul.

The largest data storage companies are making attempts to use renewable energy and otherwise reduce their carbon footprint (though that can be done by purchasing carbon credits rather than making direct use of renewable energy). Six major cloud brands (Apple, Box, Facebook, Google, Rackspace, and Salesforce) have committed to powering data centers with 100% renewable energy by 2020.

Of course, renewable energy may have its own unintended consequences. While the direct result of the technology—wind, solar, water—may have a net zero or very low carbon footprint, like the buildings that house server farms, they are not without carbon-related factors. What must be considered, especially as renewable energy technology increases in scale, are factors such as the materials used, the manufacture of the devices, site acquisition and preparation, transportation to and installation at the site, maintenance—all of this on top of the costs (in dollars and CO2) of operating the electrical distribution system and the internet, since the largest wind and solar farms, and hydroelectric plants are far from the places where the electricity generated is needed. Also, think of the potential consequences as renewable energy generation requires more land. It is hard to imagine it as a zero-sum game.

Thinking small, learning from the past

While large-scale solutions are often the only resort, despite the associated environmental costs, I wonder about the alternative of small-scale, local solutions when that is an option. I don’t recall the details, but a PBS program on energy pointed out how one appliance manufacturer found that installing a large wind turbine at the factory made sense in controlling energy costs.

Moving to examples at the level of the individual house, years ago I was interested in solar energy, but our house faced the wrong direction and, frankly, solar at that time had a long way to go to be practical, whether it was used for generating electricity or hot water. However, with a big yard and garden, I developed a multi-bin compost system and later added multiple rain barrels at the back of the house. More recently, advances in computer technology--especially flat screen monitors— converstion to LED bulbs throughout the house, and similar measures have dramatically cut electric consumption. There are ways each of us can demonstrate environmental stewardship.

As solar and wind devices have become much more efficient and adaptable to smaller settings, it is possible to think of using them for individual homes, subdivisions or communities. This futuristic vision, however, is not new.

Kline Creek farm is an 1890s farm near us that has been preserved and used to show what life on the farm was like back then. For all the modern talk of sustainability and attention to the environment, I am always impressed with how self-supporting that farm was. For example, a windmill pumped water into a tank that kept milk cans cool while waiting to be taken to market. From there the water flowed downward to fill water troughs for the animals in the barn and on to outdoor pens. A detached summer kitchen kept heat out of the house during hot months, while the kitchen stove helped provide heat inside the house in cold months. A cistern under part of the house collected rainwater to provide “grey water” for washing and bathing.

Why not use that sense of self-sufficiency and sustainability closer to home?

Back to the Cloud

Ok, I’m drifting away from the focus on The Cloud, but all these issues of resource use are interconnected. Besides, even if electric generation could be done closer to where it is used, the very nature of the internet requires vast infrastructure to connect the world.

For a good overview on this complex issue, see the infographic “The Carbon Footprint of the Internet” on climatecare.com.

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: December 353, 2018 Accessed 2,682 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...InfoMatters

Category: General / Topics: Internet • Planning • Policy • Science & Technology • Social Movements • Trends

Unintended Consequences, Number 3

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: December 353, 2018

#MeToo, Cybercurrency, and the Cloud

Social movements and innovation, while aimed at progress or correction, often have unintended consequences that blunt their impact or, in some case, make matters worse. This is the latest in a growing collection of blogs on the subject. It was inspired by two things: a recent column by Kathleen Parker on the #MeToo movement, and a discussion about cybercurrency in an adult class at the church I attend.

The inevitable unintended consequences of #MeToo

That was the title of Kathleen Parker’s December 4 column in the Washington Post. Here is an excerpt:

A recent Bloomberg News headline came as no surprise: “Wall Street Rule for the #MeToo Era: Avoid Women at All Cost.”

In a word, it was inevitable. Some men are so concerned about the possible repercussions of what they might say or do that they’re steering clear of women in the workplace altogether. And as a result, according to the report, Wall Street “risks becoming more of a boy’s club, rather than less of one.”

The article focused on the various ways some senior executives in finance have been “spooked” by #MeToo and are “struggling to cope” — resorting to staying on different hotel floors from women when on business trips, not dining alone with any woman 35 or younger, leaving an office door open when meeting one-on-one with a junior female. Generally speaking, these might not be such bad rules but for the fact that, as Bloomberg News pointed out, young women often need mentors to advance and female executives are far scarcer than men on Wall Street. And as one wealth adviser said, simply hiring a woman has become “an unknown risk.”

The story called these collateral adjustments the “Pence Effect,” referring to Vice President Pence’s personal rule of not dining alone with a woman who isn’t his wife.. . . Further, to be fair, these newly devised workplace protocols are not primarily a function of paranoia but of reality. . . . Even casual interactions can seem unnecessarily risky.And this new reality isn’t limited to the world of finance. Many men across all industries now fear being alone with a female colleague.

. . . Perceptions have changed significantly the past several decades, for the good, but we still have much work to do in defining what is and isn’t “abuse.”

In many ways, this is all new terrain for us societally: How do we balance the right of every individual to be believed innocent until proven otherwise, while also giving accusers a platform to be heard? The recent Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Brett M. Kavanaugh highlighted the impossible position of being forced to prove one’s innocence against accusations backed by no verifiable evidence. We should sleep uneasily in the wake of such an abuse of due process, not as a legal matter but as a time-honored principle of fairness.

We’ve yet to see the full spectrum of collateral damage to come, but we’ve gotten a sense of its scope. Already, some men are silencing themselves rather than engaging in a losing battle. Several have told me that, like the wealth adviser Bloomberg News interviewed, they’re more hesitant to hire women or even to be alone with them. My orthopedist tells me he’s no longer comfortable hugging his patients, as he’d always done. . . .

Many men are so intimidated by the #MeToo movement and the plausibility that they, too, could be ruined on the basis of a single woman’s misinterpretation of an innocent gesture that they’re essentially shutting down and stepping away. Suffice it to say, this side effect won’t serve women well in the long run. Indeed, it seems obvious that they’ll suffer.

There surely is a balance to be found lest the sexes further alienate and segregate. We should seek it with a sense of urgency.Read more from Kathleen Parker’s archive, follow her on Twitter or find her on Facebook.

Read more (from Parker’s online column):

Karen Tumulty: To the president, #MeToo is little more than a punchline

Daniel W. Drezner: #MeToo, one year later

Katharine Viles: I’m a sexual assault survivor. #MeToo is incredibly isolating.

Karen Tumulty: We’ve seen #MeToo gains. But also how fragile they are.

Jennifer Rubin: #MeToo needs to become #NotHim

Money without a bank

Cybercurrency (bitcoin and similar approaches) was the topic of one of the sessions in a class on “Living as a Christian in the Modern World” at the church I attend. The series has looked at social media, artificial intelligence, transhumanism, and other technological and philosophical movements affecting our culture and the impact on the expression of Christian faith. (My November 21 blog, “Driven Apart or Drawn Together,” relied in part on an earlier session on social media and public life).

Cybercurrency is a system that allows transactions of value without using traditional financial institutions. Reference was made to a technical white paper by Satoshi Nakamoto, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.” In the Abstract, Nakamoto explains the system:

A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online

payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution. Digital signatures provide part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required to prevent double-spending. We propose a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network. , , ,

The exchange of cybercurrency relies on a system of verification that avoids the banking system, but instead uses a technological solution to verify that the sender, recipient, amount and other details are valid. The approach is also known as “blockchain.” Worthy of additional discussion is the lack of trust in traditional institutions inherent in cybercurrency (dealt with, to some extent, in my March 6 blog on Trust.)

To put it simply (but risking technical inaccuracy), a long code—like a riddle—is sent to thousands of computers connected by the internet into a peer-to-peer network. Such a network is like a virtual supercomputer made up of many computers scattered around the world, all trying to solve the “riddle” for each transaction.

It is a brute force method that requires trying every one of billions of variations until the one that fits is found. Think of trying to guess a four-digit PIN number. There are 10,000 possibilities using numbers alone. If instead of numbers the code is made up of the full range of 256 numbers, letters and symbols that could be assigned to each position, the possibilities increase to 4,295,000,000. The cybercurrency riddle has so many possibilities, it can take up to ten minutes for all the computers active on the peer-to-peer network to find the correct solution. Only then can the transaction be authorized. The “node” finding the solution is awarded a fee.

When a flow chart depicting the process of a cybercurrency transaction was displayed, my eyes fell on the verification step that uses this large peer-to-peer network. With the amount of distributed computer power required, I wondered, “what is the carbon footprint” of verifying bitcoin and similar transactions?

Even if we’re talking about a bunch of people who each have only a few computers in their basements, consider the cumulative amount of computing power needed to solve all those riddles (transactions) each day. That translates into a lot of electrical power and heat. It may not be much at any one node on the network, but taken together, it could be comparable to or even exceed that of an actual supercomputer. (A supercomputer is not used, as I understand it, because the verification system relies on the independence of the distributed nodes).

The cybercurrency approach is supposed to be hacker-proof, though I wonder with others if the enormous interest shown by nation-players like Russia and China to “weaponize” the internet will keep that claim an absolute certainty. (See the section on “The Darkening Web” in my blog on Trust.) As I was finishing this blog, a report on Nightly Business Report focused on this very type of attack by the Chinese, using “crypto-mining.”

One of the consequences (unintended, hidden or ignored) of cybercurrency is the carbon footprint of the aggregate resources necessary. The irony is that many people enthralled with technology and concerned about climate change, are either unaware or ignorant of the impact of their own activity. The introduction of “The Cloud” is similar.

The carbon cloud

What comes to mind when you think of “The Cloud”? It has a magical ring. It sounds very innocuous. The Cloud is a term applied to a collection of large capacity data servers connected to the internet. The net effect is to move data from individual computers and networks to the internet, where it can be more easily accessed across devices and users.

While “the cloud” connotes a single, mammoth “server farm,” it is made up of numerous server farms around the world, each containing row upon row of racks filled with storage and routing devices, all connected by the internet. It is a concept that has taken on a cool nickname that obscures its true nature, which is that the data is now “out there,” somewhere and not on your local device. (It is possible to maintain a local copy and synchronize it with the cloud version. It is now common for software to give the option of local and/or cloud storage.)

Ever-increasing bandwidth (data-carrying capacity) of the internet along with faster and more powerful devices (from computers to smart phones) and cheap storage for ever-larger amounts of data have led to the exponential growth in the number of servers that make the cloud as ubiquitous as it is. That is where the unintended (or ignored or tolerated) consequences come in.

Moving data from your own computer to the cloud means it is going to a server farm, usually housed in a large building. That means a “brick and mortar” structure along with large amounts of electricity to power the servers and the air conditioning to cool them, with a significant carbon footprint. A friend mentioned driving around an industrial park and seeing what looked like a huge warehouse, except it did not have the usual row of loading docks. It was a server farm for Amazon.

I remember reading several years ago about Google’s plan to use barges as a location for server farms that could be water-cooled instead of requiring traditional energy-hungry air conditioning. (See “Google’s worst-kept secret: floating data centers off US coasts” in The Guardian, October 2013).

The issues discussed here are admittedly very complicated. You’ll find articles outlining the huge carbon costs of the cloud and internet while others suggesting that such technology can reduce carbon emissions, at least in the long haul.

The largest data storage companies are making attempts to use renewable energy and otherwise reduce their carbon footprint (though that can be done by purchasing carbon credits rather than making direct use of renewable energy). Six major cloud brands (Apple, Box, Facebook, Google, Rackspace, and Salesforce) have committed to powering data centers with 100% renewable energy by 2020.

Of course, renewable energy may have its own unintended consequences. While the direct result of the technology—wind, solar, water—may have a net zero or very low carbon footprint, like the buildings that house server farms, they are not without carbon-related factors. What must be considered, especially as renewable energy technology increases in scale, are factors such as the materials used, the manufacture of the devices, site acquisition and preparation, transportation to and installation at the site, maintenance—all of this on top of the costs (in dollars and CO2) of operating the electrical distribution system and the internet, since the largest wind and solar farms, and hydroelectric plants are far from the places where the electricity generated is needed. Also, think of the potential consequences as renewable energy generation requires more land. It is hard to imagine it as a zero-sum game.

Thinking small, learning from the past

While large-scale solutions are often the only resort, despite the associated environmental costs, I wonder about the alternative of small-scale, local solutions when that is an option. I don’t recall the details, but a PBS program on energy pointed out how one appliance manufacturer found that installing a large wind turbine at the factory made sense in controlling energy costs.

Moving to examples at the level of the individual house, years ago I was interested in solar energy, but our house faced the wrong direction and, frankly, solar at that time had a long way to go to be practical, whether it was used for generating electricity or hot water. However, with a big yard and garden, I developed a multi-bin compost system and later added multiple rain barrels at the back of the house. More recently, advances in computer technology--especially flat screen monitors— converstion to LED bulbs throughout the house, and similar measures have dramatically cut electric consumption. There are ways each of us can demonstrate environmental stewardship.

As solar and wind devices have become much more efficient and adaptable to smaller settings, it is possible to think of using them for individual homes, subdivisions or communities. This futuristic vision, however, is not new.

Kline Creek farm is an 1890s farm near us that has been preserved and used to show what life on the farm was like back then. For all the modern talk of sustainability and attention to the environment, I am always impressed with how self-supporting that farm was. For example, a windmill pumped water into a tank that kept milk cans cool while waiting to be taken to market. From there the water flowed downward to fill water troughs for the animals in the barn and on to outdoor pens. A detached summer kitchen kept heat out of the house during hot months, while the kitchen stove helped provide heat inside the house in cold months. A cistern under part of the house collected rainwater to provide “grey water” for washing and bathing.

Why not use that sense of self-sufficiency and sustainability closer to home?

Back to the Cloud

Ok, I’m drifting away from the focus on The Cloud, but all these issues of resource use are interconnected. Besides, even if electric generation could be done closer to where it is used, the very nature of the internet requires vast infrastructure to connect the world.

For a good overview on this complex issue, see the infographic “The Carbon Footprint of the Internet” on climatecare.com.

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: December 353, 2018 Accessed 2,683 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...